Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

A recent series of immersive workshops allowed students from all disciplines to sample a career in crime scene investigation.

Dec. 2, 2025

Wilfrid Laurier University’s Brantford campus is no stranger to film and TV production crews, but when Assistant Professor Nathan Vo’s labs were recently transformed into a crime scene, it wasn’t for a new season of Bones.

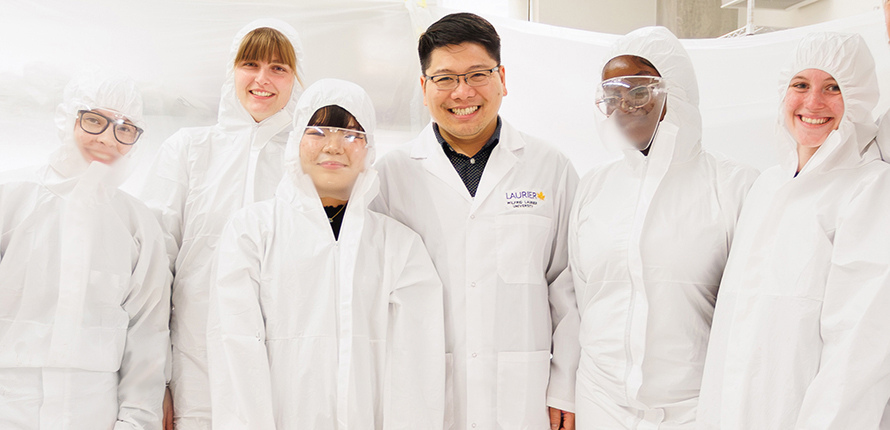

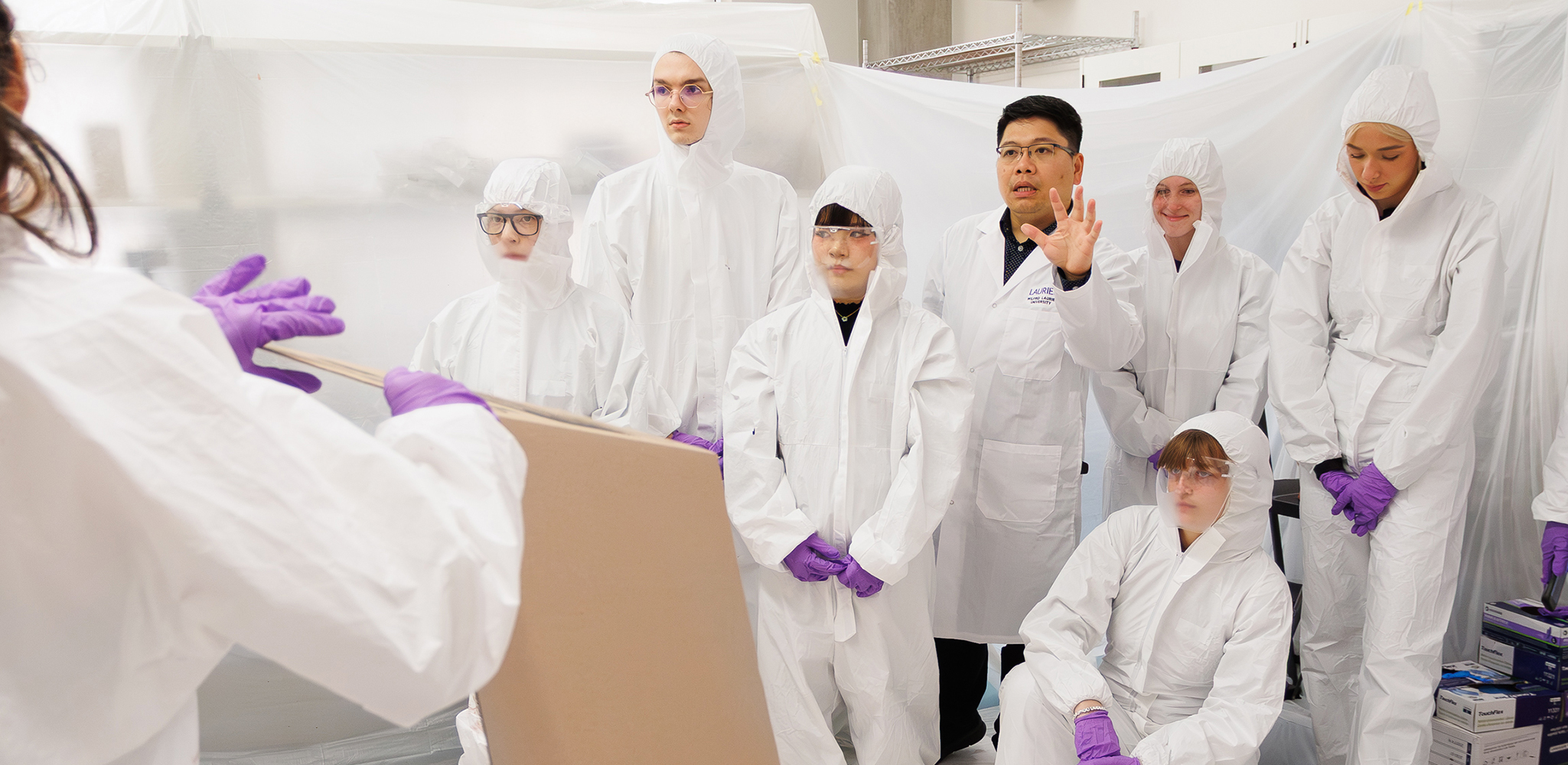

Although the set dressing had all the hallmarks of a pulse-pounding police procedural — complete with floor-to-ceiling plastic sheeting and evidence bearing suspicious rust-coloured stains — there was one key difference. The technicians in Tyvek coveralls and nitrile gloves weren’t actors, but students, seizing a unique opportunity to experience the realities of crime-lab work.

Presented by Vo and Laurier Brantford’s Criminology Student Association, “Blood Stains and Blood-Spatter: Inside a Crime Lab” invited Brantford campus students to step into the shoes of a forensic scientist in a series of hour-long workshops. Led by Vo and his team of student researchers, participants gained immersive experience analyzing bloodstain patterns and taking swabs of evidence for forensic testing.

“We created this event to engage our students in forensic education and to give them the opportunity to get hands-on, practical training,” says Vo. “It was meant to be fun and educational at the same time, and I think we succeeded.”

Vo, who has been teaching in Laurier Brantford’s Department of Health Studies since 2022, partnered closely with Criminology Student Association president and third-year Criminology student Mariyo Al-Deero in developing the workshops. Both saw the lab-based approach as a natural complement to Vo’s in-class lectures.

“This is a nice way of offering an interactive, experiential learning component to my first-year course, Introduction to Forensic Science,” Vo says. “After all, experiential learning is what Laurier is known for.”

Initially conceived to serve Laurier’s Criminology community, Vo and Al-Deero ultimately decided to open registration to students across the university, and were blown away by the response. More than 90 students in programs from Health Studies to User Experience Design took part in workshops held the week of Oct. 20, a testament to the vibrancy of the Brantford campus and the broad appeal of the subject matter.

“We watch Criminal Minds and CSI and we’re fascinated not only by crime, but by how science is applied to help solve forensic cases,” says Vo. “It’s an innate curiosity about how natural sciences are used to help collect and interpret evidence, piecing everything together to solve a mystery.”

“One of Laurier’s strategic priorities is future-readiness. As faculty members, we try to provide not just theories and concepts, but also opportunities for experiential learning where students can develop skill sets that prepare them for the workforce.”

Assistant Professor Nathan Vo, Department of Health Studies

For Al-Deero, who is minoring in Physical Forensics, the workshops represented a paradigm shift in his studies.

“In my own Criminology courses, we’ve been using a theoretical framework to analyze and explain crime. These workshops give you a different perspective: a scientific approach where there’s no room for interpretation and just one right answer,” says Al-Deero. “It strikes a balance between theory and science.”

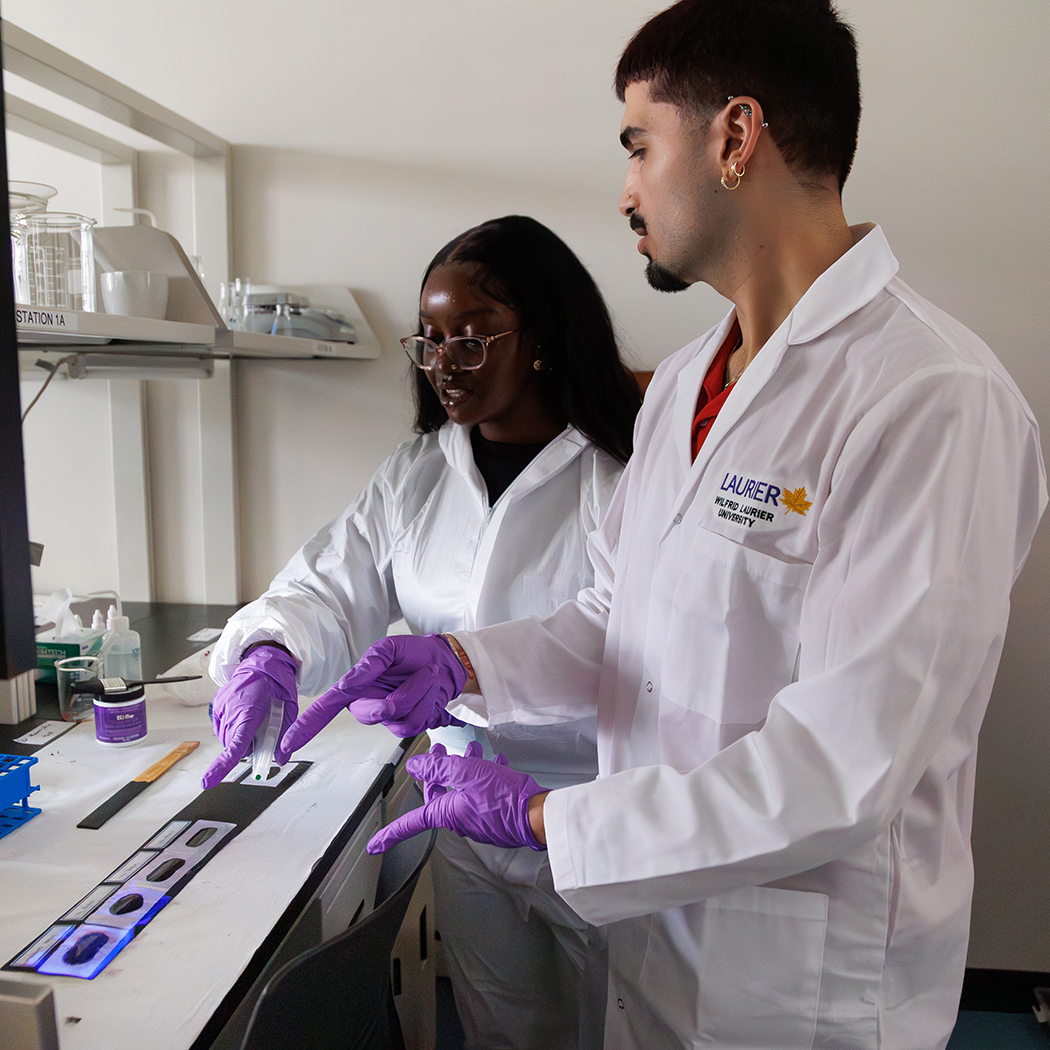

Each of the workshops was split into two half-hour sessions, one focusing on forensic blood tests, the other on blood spatter analysis.

In the forensic blood test lab, participants used swabs to collect samples from a mock crime scene exhibit — in this case, a stained cabinet door — and conducted three tests that are essential in a forensic investigator’s toolkit. Known as presumptive tests, these procedures are used to quickly identify the possible presence of blood, which is later verified through confirmatory testing. In the Kastle-Meyer and Hemastix tests, participants witnessed the sample trigger a colour-change on the swab or test strip, respectively, indicating the possible presence of blood. The third and most dramatic test involved spraying the evidence with a substance called luminol, which causes blood-stained surfaces to glow as if under a black light. Through additional demonstrations, participants were shown that luminol can even reveal stains on surfaces that have since been painted over, as well as on clothing that’s been laundered several times.

For third-year Criminology student Taylor Faber, who’s minoring in Physical Forensics and Psychology, the opportunity to take part in these demonstrations was reason enough to register for the event.

“I’d learned about presumptive tests in my Intro to Forensics class, but I hadn’t actually performed them or even seen them in real life until I attended the workshop,” says Faber. “Working with the luminol was really cool. I felt like a real forensic scientist.”

Across the hall in the blood spatter lab, participants had to rely not on chemical reactions, but their powers of forensic pathology to read the clues.

“Our blood spatter lab is the same kind of setup you’d expect to see in the Ontario Police College, used to train police officers and detectives how to look at blood stains, patterns and spatter, and use that to inform how a victim was attacked and what kind of weapon was used to cause the injury,” says Vo.

Here, using commercially sourced horse blood, which is a close match to the viscosity of human blood, students learned that a drop of blood that’s circular in shape likely fell at 90 degrees, indicating no force other than gravity was involved, making it a “passive” bloodstain. An elliptical drop of blood, on the other hand, with a clearly defined head and tail, yields more information, hinting at the direction — and intensity — of the impact.

As one of Vo’s student researchers and workshop co-presenters, fourth-year Criminology student Tayha Artinger took a lead in instructing participants in deciphering these patterns. She says the workshops’ immersive approach countered pop culture depictions of both crime and forensic research with a healthy dose of realism — and humanity.

“Violent crimes tend to grab the media’s attention and there’s the risk of criminal incidents being glamourized,” says Artinger. “These workshops make it very real. People’s lives are affected by these crimes and it’s hugely important to be sensitive when you’re working with victims and survivors.”

For participants like Faber, the workshops exceeded all expectations and provided an invaluable addition to her resume.

“I gained real-world experience,” she says. “If I decide to work in law enforcement or evidence collection, I’ve got a foot in the door understanding how these tests work and how they might be admissible in court.”

The workshops were also a learning experience for Vo’s student researchers, many of whom had no prior experience leading labs for their peers.

“It was a little nerve-wracking at first, but after the first few sessions, I became more comfortable presenting in front of the groups,” says Artinger. “It only furthered my passion for the subject.”

Much of the enthusiasm shared by the event’s participants and presenters can be traced back to Vo himself. A recipient of the Ontario Minister of Colleges and Universities’ Award of Excellence for university teaching, Vo’s ability to make complex scientific concepts accessible has earned him the admiration of students in the classroom, and now, through these workshops, even beyond it.

“He's super engaging,” says Artinger. “He clearly cares about every student who takes his courses and does his best to make sure you come away with something new after each lesson.”

In turn, Vo says he’s inspired by his students’ insatiable thirst for answers.

“As a scientist, I often look for curiosity in students,” he says. “I believe strongly that curiosity paves the way for innovation. Often, when students are curious it also makes me more innovative in terms of making the course materials more interesting and the experiments more exciting.

“Our students at Laurier Brantford are fantastic. They’re here to learn, to take something with them and to create new ideas and inventions. As long as we as faculty are able to stimulate them and challenge them to ideate, there’s no stopping them.”